There is a Norwegian author named Karl Ove Knausgård who has embarked on a literary project somewhat similar to that of Proust's. In six volumes, counting 2500 pages, he writes about the whole of his life from childhood to today - though he is no more than forty. The style isn't quite as enveloped and enveloping as Proust's (a good thing, surely, as this work is actually a hundred years) and, funnily enough, far more prosaic. At least on the surface.

There is a Norwegian author named Karl Ove Knausgård who has embarked on a literary project somewhat similar to that of Proust's. In six volumes, counting 2500 pages, he writes about the whole of his life from childhood to today - though he is no more than forty. The style isn't quite as enveloped and enveloping as Proust's (a good thing, surely, as this work is actually a hundred years) and, funnily enough, far more prosaic. At least on the surface.

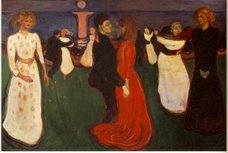

Only the first volume has been published, but two more will follow before christmas; one in October, one in November. The last three probably in January, February and March. (If anyone is cunning in Germanic languages, they will notice a concordance with the title on the picture to the right to the work of an infamous

Austrian some 70 years ago. An edge the author obviously wanted to his already quite noticeable endeavour. He is certainly not afraid to be called pretentious, and has also called this project a "literary suicide". As this theme demands a whole post of its own, I am continuing on a different note.)

I'll have to admit at once that I have not yet read this latest book of Knausgård's, but I am probably going to as I have read all (two!) previous books of his. Just the first page. But often you can get a sense of the whole work just by reading one page.

Like Proust, Knausgård introduces his hexalogy with a sentence easy to remember: "For hjertet er livet enkelt: det slår så lenge det kan." Or in English, something like this: "For the heart life is simple: it beats as long as it can" (pretty direct translation, no work of an expert). In Norwegian this sentence has a rhythmical drive, a simplicity in sounds and words, yet at the same time a poetic edge made out of words as basic as stick and straw, water and stone. What follows in this opening paragraph is a detailed, physical description of human death. Detailed, but still with that literary voice trailing behind, leading the prosaic (though dramatic) course to its end.

Proust's opening sentence is one of the most famous in the history of literature: "Longtemps, je me suis couché de bonne heure" - or "For a long time, I went to bed early." As we know, Proust has forever linked his name to the little dry bisquit called madelaine. I remember listening to a radio programme sometime around my twelfth year, hearing a woman speak passionately about an author who wrote in these marvellous sentences which stretched over two pages, and how he could describe the taste of a cake through pages and pages - and I remember really longing to find out how this literature was. Sadly the lady in my radio never mentioned the author's name from the time I got to listen to her, but I feel quite sure that it must have been Proust she was going on about. The joy of being presented with this strange and unknown literary master was almost greater than that of years later finding out who this person was, and later still to read some of his prose.

This simple yet alluring opening sentence reminds me of what often pulls me into a book: a taste of the author's very own universe, with the novel's specific tone included. Isn't this the reason we read books? To be enveloped in a strange but somehow familiar world where time is most relative and you are in a strange position between being the master of deciding the world's progress (as you decide when to pick up the book an break it off) as well as being led by the hand through a story you have no control over. "The world moves in appetency on its metalled ways", Eliot would have put it ("Burnt Norton" III).

A good example of first sentences which also says a great deal about the rest of the book is the beginning of Jane Austen's Emma: "Emma Woodhouse, handsome, clever, and rich, with a comfortable home and happy disposition, seemed to unite some of the best blessings of existence; and had lived nearly twenty-one years in the world with very little to distress or vex her." In this rather long sentence, we are introduced to the main character and the story which will unroll almost directly from her characteristics. This is a character-driven story with Emma in the thick of every twist and turn of the intrigues; she is actually the embodiment of the plot.

I love the idea of opening a book on any given page and getting the flavour, or almost the whole idea, of a book. And this flavour is probably strongest on the first page, where the author holographically presents his project to you, the reader. One can become incredibly wealthy feasting on brilliant minds. So subsequently, which place to go expand your mind-wallet beats the library?